|

A new economics and integrated business model is possible.

This is a

non-authorized back-up-copy for blog-reasons You may find the original text at http://www.southerndomains.com/southernbanks/index.html

and more precise at http://www.southerndomains.com/SouthernBanks/p2.htm

Smith, Marx, Kondratieff and Keynes:

Their Intellectual Life Spans, the Convergence of

their Theories based upon the Long Wave Hypothesis and the Internet Broadway @ 50th Street, NYC

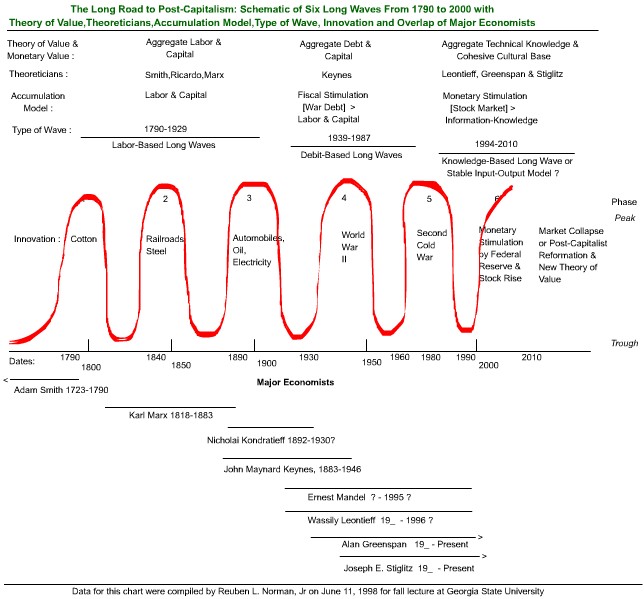

1. Introduction Chart 1 First Three Long Waves as

Defined by Kondratieff

The central economic question from the dawn of capitalism in the late 1700s has been over the stability of the relationship between production and consumption. There have been roughly three answers to this question, yes, no and maybe. Adam Smith claimed a completely harmonious relationship, Karl Marx claimed a completely contradictory relationship while two other economists, Nicholai Kondratieff and John Maynard Keynes, fell between the two extremes. The one constant between these views seems to have been a common acceptance of the labor theory of value, although not always explicitly stated, but with different beliefs in the labor theory's implications for the production-consumption ratio and monetary policy. In short, Smith believed that production could never greatly exceed consumption, while Marx believed that production would catastrophically outstrip consumption. Kondratieff believed in a long term- but cyclical- stability within capitalism over forty to fifty year time spans with serious periodic depressions. Kondratieff felt that there was an internal restabilizing factor within capitalism, which reasserted itself during serious depressions, with each major down turn holding within itself the seeds for the next upturn. Keynes knew that capitalism could build more capacity than it could absorb. However he believed that these imbalances could be resolved through 'counter-cyclical' deficit speeding by the federal government. For Keynes, the weak point of capitalism lay within investment, and serious depressions made further private investment difficult, opening the door to direct federal intervention through the 'counter-cyclical' deficit spending. This type of intervention has become known as fiscal and monetary policy. This paper attempts to show a convergence of these seemingly oppositional approaches through the common denominator of the labor theory of value. Thus Smith created the labor theory of value to describe how a small village economy worked, but Marx later showed the consequences of how the labor theory would function within a larger capitalist system, leading to excess production and a serious economic downturn, followed by a political collapse. Kondratieff believed that periodic downturns were resolvable within capitalism. Other long wave writers suggested that new labor-based innovations brought capitalism out of the serious depressions, in effect reestablishing the labor theory for another period, of perhaps twenty years. The 1920s experienced a different type of innovation, more accurately, the reapplication of an earlier invention electricity, to the assembly lines.1 Electricity-based changes to the assembly lines allowed total manufacturing output to increase, while decreasing the number of manufacturing workers. A similar trend occurred on the farms simultaneously. The increase in productivity of almost fifty percent over five years during the early and middle 1920s allowed profits to rise, driving the stock market forward during 1928 and 1929. Yet as wages failed to keep up with productivity, overproduction increased and a mountain of inventory arose, leading into the Great Depression.2 The Great Depression marked the end of conventional labor-based, innovation-driven long waves. Innovation during the 1930s continued the model of the 1920s and was more oriented to decreasing the number of workers by individual companies, in a partly successful attempt to maintain short-term corporate profitability by decreasing labor costs. The countrywide effect was that production continued to exceed consumption throughout most of the 1930s. The description of this economic collapse by Keynes was 'secular stagnation.' Keynes attempted to use federal deficit spending to reemploy out-of work labor, thus in effect refloating the labor theory of value until private investment could restart and support the labor theory again. Only worldwide war gave Franklin Roosevelt the political power to wrest control over 1920s-1930s-investment model from the corporate sector and direct investment in such a fashion as to rebalance production and consumption through the war. This model of debt-driven consumption continued after 1945, ending approximately in the stock market crash of October 1987. There Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan began guiding the economy out of the labor theory of value, towards some new amorphous model. As Internet usage began accelerating in the early 1990s, the outline of a post-labor economy began coming into focus. The conclusion of the paper seeks to show how the information-knowledge revolution over the Internet is finishing off the Roosevelt-Keynesian solution to the 1930's stagnation, probably eroding the labor theory of value permanently and thus destabilizing all previous explanations for capitalist development. The paper seeks to lay a foundation for a new monetary system, based in converting large amounts of knowledge-induced or knowledge-directed goods and services into consumption.3 Each of the four economists wrote in different parts of

the world and in very different economic times, with little intellectual

overlap during their respective working periods. Capitalism was an

evolving phenomena, which each economist described to the best of their

abilities during their lifetimes. Each economist's interpretation was

influenced by the channel of information, which was then available, and by

the relative development of capitalism itself. In the classical era of the late 1700s, Adam Smith believed that an 'invisible hand' kept production and consumption together. Human labor provided both the production as well as monetary value necessary for consuming the output of others in the village. This 'labor theory' of value as described by Smith and later by David Ricardo, simply stated that the number of hours of human labor involved in the production of an article largely determined its market price. Sixty years later Karl Marx, using this same labor theory of value, claimed that capitalism was inherently incapable of providing enough total buying power to keep production recycling into consumption: He

[Marx] took over the analytic framework of classical political economy

[Smith and Ricardo] Marx believed that not enough monetary value was being transferred to the working class to maintain the long-term balance between production and consumption. He believed that production would ultimately so outstrip consumption that the resulting instability would lead to a revolution by the working class in the advanced industrial countries. Writing during the 1930s, British economist John Maynard Keynes believed that 'overinvestment' could lead to excessive productive capacity and that the national inventory could get ahead of total consumption power. The whole economy could almost stop, as was the case during the Great Depression. However, Keynes believed that the solution for such a period of stagnation was for the federal government to run deficits, stimulate consumption and restart production. 3. Long Waves and the Contradictions between Smith, Marx and Keynes The seeming contradictions between Smith, Marx and Keynes can be resolved however by reference to another less well known idea, the 'long wave' theory associated with Nicholai Kondratieff. 5 This idea can be compared with an elongated business cycle, but this was not Kondratieff's intent. Kondratieff was writing in Russia before World War l and around 1915 was publishing his theories. These forty to fifty year 'long waves' represented the rise and fall of the overall capitalist system. Kondratieff was somewhat unclear as to the exact cause of the long waves. Kondratieff believed that starting around 1790

capitalism had had two complete 'waves' of economic growth and decline,

with a third wave rising in the early 1900s. Schumpeter believed that each

of these waves had been associated with a substantially new labor-based

innovation, which had in turn increased employment. Here are the

innovations and approximate starting dates of the first three long waves

as defined by Kondratieff. ________________________________________________________________________ Chart 1 First Three Long Waves as Defined by

Kondratieff Wave Innovation Starting Date 1

Cotton

gin and clothing manufacturing

1790 ________________________________________________________________________ Each of these long waves created very wealthy families. Thus the railroad and steel families included the Astors and the Carnegies. Thus the oil and automobile dynasties included the Rockefellers and the Fords. Later during the 1930s, Joseph A. Schumpeter revised Kondratieff's theory and claimed that the capitalist entrepreneur was responsible for particular labor-based innovations, which then precipitated the long waves. The version of long wave theory presented here is a conflation of Kondratieff and Schumpeter. This version suggests that periodic severe depressions in capitalism have been relieved by new labor-based innovations, less than through the wringing out of bad debt through debt-deflation as claimed by conventional economics. 6 The long wave collapses have occurred in the way that Marx described. However, so long as new labor-based innovations have developed, capitalism has rebuilt itself each time from each collapse. 4. Major Modern Economists and Their Long Wave Overlap The development of a long wave theory or a business

cycle theory could not have occurred prior to the existence of more than

one such long wave or cycle and the development of sufficiently strong

databases to supply the evidence for such a theory. The economic data

which has existed for much of the twentieth century and which formed the

basis for the long wave theory of Kondratieff, did not exist during either

Smith's or Marx's era. Thus Adam Smith could scarcely have imagined any

type of cyclical theory, based in modern economics. 7

Thus Marx lived and wrote during the long wave down turn of cotton-based

manufacturing and the upturn of the steel-based railroad long wave. Yet,

an economic database to explain either long wave did not exist. All Marx

had to consider was his theory of capitalist development, the labor theory

of value, the 1840-1850s economic problems and whatever anecdotal economic

evidence he could find in the newspapers of his era. ________________________________________________________________________ Chart 2 Major Modern Economists and Long Wave

Overlap with Their Life Spans Economist

Life

Dates Long

Wave Overlap Karl

Marx

1818-1883

1:

Cotton manufacturing; N.

V. Kondratieff

1892-1930 ?

2:

Railroads and steel;

________________________________________________________________________

5. Production Consumption Balance and the Long Waves Adam Smith wrote the first major description of village-level capitalism in 1776, The Wealth of Nations, the same year as the start of the American Revolution. In it, Smith described how an 'invisible hand' seemed to balance out the productive capacity of the village with its consumptive needs. The clear implication was that production and consumption would by and large stay in balance, again with guidance of the 'invisible hand'. His interpretation of economics was colored by the fact that modern capitalism had just begun, and the 'invisible hand' did indeed function at least somewhat as he described it. However, the first long wave economic boom was not even on the horizon. When Smith wrote, knowledge was hardly a factor the economy, his 'invisible hand' idea implied that knowledge didn't really matter. Marx was writing by 1850 and died in 1883. He lived most of his life during the first long wave based upon cotton manufacturing. He saw an entirely different industrial capitalism, than the village-based capitalism of Smith. His life did not end during the first long wave, but his theoretical views were formed by it. He was unable to see beyond the general tendency of capitalism to eliminate human labor and increase machine-based debt in the production process. Thus he believed that the equivalent of a single long wave would rise, crest and fall, dragging capitalism down with it. Marx lived to see the first long wave fall and the revolutions of the 1850s, but could not understand how a second labor-based wave might get started and restabilize capitalism. Marx was alive as the second long wave based upon railroads and steel started, but died before it had crested and fallen. Kondratieff was writing near the start of the 1900s and

his major theory was published in the United States around 1926. He lived

after the two long waves of the 1800s had risen and fallen. Thus the

cotton manufacturing era and the railroad era had come and gone by the

time Kondratieff was forming his economic views. And a third long wave was

making serious progress, that of automobiles, highways and electricity.

_________________________________________________________________________ Chart 3 Major Modern Economists with their

Life Dates and Economic Assumptions on

_________________________________________________________________________ Kondratieff contradicted Marx, in that he claimed that capitalism was in fact regenerating itself through periodic waves of upward movement after periods of downward movement. What defined these upward movements was an internal ability of capitalism to develop new innovations, which then pulled labor back into the production process after a long wave crash. 9 There seems to be an implicit acceptance of Marx's analysis of the internal workings of capitalism, but a revision of Marx concerning periodic new labor-based innovations and upwards swings in the economy. Kondratieff did not set forth a theory for the long wave, although he did note that innovations developed during the down side of one long wave were often later used the next upswing.10 After the collapse of the third long wave into the Great Depression in 1929, Stalin imprisoned Kondratieff and he probably did not live to see the resuscitation of capitalism through a war financed with massive fiscal debt, as hypothesized by John Maynard Keynes. 6. Keynes, Secular Stagnation and the Great Depression John Maynard Keynes was a young man at the World War l Paris peace talks in 1919. He had written a devastating analysis of the likely results of the Treaty of Versailles upon the German economy. 11 The

Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) met with a reception that makes

the word The

pure theory of business cycles was never one of Keynes' primary interests.

In this What in fact Keynes was trying to remedy was the crash of the third long wave of automobiles and electricity. Unfortunately no new labor-based innovation was ready to restart employment. Moreover, something unique to capitalist development had occurred on the assembly lines during the early 1920s, a technique which permitted output to increase even with a declining number of workers. A 1929 book by a then mainstream economist, Irving Fisher, described the 1920s situation in a nutshell, although a theoretical explanation probably could not have been developed at the time for avoiding the coming depression. Between 1899 and 1921, manufacturing output rose in congruence with increases in both horsepower and workers, but after 1923, output rose even with a gradual decline in the workforce. 16 Thus for the first time in the history of modern capitalism, an innovation was put into the system which permitted rapid increases in productivity and total manufacturing output- simultaneous with declines in the number of workers providing the labor. This was an extremely radical event. At first it drove up the price of stock- since above average profits were possible from companies employing the new technology. But after the collapse of 1929, the new technology permitted the monopoly manufacturing companies to gradually decrease their worker level and yet maintain roughly the same or perhaps higher output. Even in a situation where production was declining, these techniques would allow the necessary labor to drop even more rapidly than the level of production, thus allowing the companies a chance to keep profits from collapsing completely. This combined with the lack of a new labor-based innovation was a major reason, if not the major reason why the economy did not begin to improve after the initial shock of the stock market crash began to wear off after several months during 1930. During previous eras of capitalism, it had never been possible to have such increases in output or the maintenance of a stable level of output, while simultaneously being able to cut the total system-wide number of workers. Thus if the number of people with wages was dropping, even as the nation-wide output was stable [or dropping slower than the rate of employee layoffs] and if those companies were able to keep their prices at roughly the same level- the system was incapable of clearing the aggregate output with the available aggregate wage income. This was and remains a good formula for creating a stagnating economy. A shift in the use of electricity on the assembly line was the prime cause of this early 1920s shift. Electricity moved from being: 1.

a consumer invention for lighting and other household uses, or into powering a completely new point-of-production assembly line system. This new point-of-production assembly line system was the reason for the radical shift in the relationship between labor usage and power increases in the manufacturing sector. This process drove total manufacturing output well beyond total consumption power in America. Thus Keynes faced two serious problems as he began trying to restart the capitalist system during the 1930s; the lack of a new labor-using innovation and the application of an innovation which was drastically lowering the labor needed in the existing sectors. Ultimately, only massive war would begin to bring consumption and production back into balance. Here Keynes would provide the democracies with an economic idea sufficient to finance the war: massive federal deficit spending. 7. Keynes: Fiscal Deficit Policy, the First Debt Wave and Monetarism Keynes accepted the reality that production could greatly exceed consumption, but he believed that the federal government could rebalance such gaps. 17 Keynes believed that 'overinvestment' could lead to a situation where too much productive capacity or 'aggregate supply' would exist for the existing wage-base or 'aggregate demand' to be able to purchase it. In such a situation, as the inventory buildup gradually forced business to layoff more and more workers, the federal government could rebalance production and consumption through deficit or 'counter-cyclical' spending. The federal government had the legal ability to run deficits, and according to Keynes, had the responsibility to do so when unemployment became a serious drag on the general economy. In Keynes' model, as business inventory was purchased by the federal government, business would again begin rehiring unemployed labor. Federal deficits would increase the monetary velocity and each dollar of federal spending might account for several more dollars of private spending. That is, the newly hired labor would again begin making purchases and shortly, the production and consumption would again be in rough balance. At that point, ideally the federal government could begin to run a surplus and pay off the debt of the previous downturn. Possibly the overlap between the currently powerful monetarists running the American, European and Japanese central banks; and Keynes lies in the question of monetary velocity, more precisely how to improve the speed of money turnover during a downturn. For the monetarists, improving interest rates should usually resolve the problem. However, Keynes was sure that some economic crises were too deep to be resolved by simply lowering interest rates and required direct federal intervention in the economy. Keynes was not convinced that interest rate policy was any more important to investors than their belief that a given level of investment would return a particular level of profit. Keynes emphasized effective demand in a complete system: 1.

household demand for consumer goods Household consumption was relatively stable, largely determined by income itself- but business investment was the weak link. Interest rates as well as profit expectations determined the rate of investment. Investors compare known interest rates with expected profit rates- to decide how much or how little to invest. 18 For Keynes, the key to understanding lay in that household consumption would almost always remain close to the levels of household income, it was almost a constant. The problem, was that investment depended upon the perception of the capitalist owners-investors, that more profits could be derived by further investment. Thus investment was not a constant, at least not private investment. High levels of private savings would not necessarily lead to equivalent levels of private investment. When for whatever reason, private investment lagged to the point where employment was in trouble, the federal government was obligated to make up for the investment slowdown. Under ideal circumstances, the federal government could provide enough economic lift to being private investment back into the market. The problem with the monetary revision of Keynes's theory is that monetary policy and interest rates alone do not determine the decision to invest by the private sector. Low interest rates will not encourage scared investors, if they do not see profits arising from investment. Thus the Japanese central bank has had its discount interest rate at one-half of one percent for many months and the Japanese economy is still sitting dead in the water, stagnating except for its increasing exports to the United States. And high interest rates will not necessarily prevent investment from occurring, if investors believe that profits can be derived above the costs of borrowing. Naturally, low interest rates are generally preferable all around- but interest rates were not the crucial element for investment. Monetarists seem to believe that the leveraging of interest rates and the money supply are the crucial elements for keeping production and consumption together. The idea that interest rates might drop too low to be a factor in corporate investment decisions, the 'liquidity squeeze' or 'liquidity trap', is not generally a part of the monetarist formula of economics. 19 Keynes died in 1946, not long after the end of World War ll. The British and Americans had run the war under Keynes's guidance and he died as the western allies were attempting to rebuild the economic foundations of capitalism. 8. Keynes's Debt Waves 1 and 2: Roosevelt to Reagan After World War ll., there was a breakdown of both

Keynes and Kondratieff's theories. First, the capitalist system did not

return to the Great Depression after the end of wartime deficit spending,

as was feared by many Keynesian economists. 20

And in contradiction to Kondratieff, the capitalist system took off on

another twenty-year boom, without another major labor-based innovation.

What I believe occurred, is that deficit spending simply shifted from the

federal government to the business and household sectors and these new

deficits or debts drove economic growth after the war. 21

This may seem like ancient history to some, but there is a point to all of this. Ronald Reagan's economy in many ways emulated Roosevelt's- in particular his massive federal deficits used to fund the moral equivalent of war, his military build-up against the weakening Soviet empire. David Stockman has commented in several places about the sheer stupidity of Reagan's economic policies and others have called it 'military Keynesianism', as if the original 'test' of Keynesianism during World War ll. was some other variety of Keynes' theory. 23 The reality is that both major applications of Keynes' theory occurred during what was considered during both occasions to have been fairly serious economic troubles. Although the unemployment rate in 1981 was not as bad as 1931, the prime rate in 1981 to 1982 was so high, that housing construction fell flat, and another year of two of such rates could have stifled automobile manufacturing as well. Moreover, both such 'tests' of Keynes' theory occurred along side large-scale military build-ups. As much by luck and ignorance as by anything else, Reagan stumbled through his first two years, then as capital began flowing inward from around the world, seeking the outrageous interest rates in America; that in combination with his military build-up kick started the economy and by 1984, it was indeed 'morning in America'. Reagan floated through his reelection and continued to run massive deficits. In October 1987, the market finally collapsed, but through the luck of history, Paul Volker had left the chair of the Federal Reserve and Alan Greenspan had moved in. Greenspan flooded the financial system with money and probably prevented a far worse collapse, perhaps a second Great Depression. Had Volker remained as chair of the Federal Reserve, it is entirely possible that he would have maintained a tight money supply and kept interest rates high for too long. It had been Volker who between 1978 and 1982 had sent the American economy into deep recession, through tight Federal Reserve policies. 9. From Labor Long Waves to Debt Long Waves to Knowledge Long Waves Again, all of this history is necessary, because the last two hundred years of economic growth have not been automatic. Growth has come and gone in fairly coherent forty-year waves. The crashes of first two waves were resolved though internal innovations, the rise of railroads in the 1850s and rise of automobiles and electricity in the early 1900s. The third crash in 1929 was resolved about ten years after it started and only through massive federal deficits funding a massive war. The fourth crash or more accurately, the slow-down in western economic growth which started around 1970; was also resolved about ten years after its start, again by a massive rise in the federal deficit starting in 1981-1982. The common feature of the crashes of the first four long

waves was that the crashes were resolved by something which put the

unemployed back to work, by stimulating investment (please see Chart 4).

The crucial ingredient to the resolution of all four previous crises has

been that paid wage employment was rapidly increased by something.

The initial long wave was probably caused by the evolution of the labor

theory of value, along side the creation of clothing manufacturing,

themselves made possible by the invention of the cotton gin by Eli

Whitney. Put into rough Marxist nomenclature, each of the first four long

wave crashes were resolved as the labor theory of value was restored, for

another period of time. Another way of looking at matters, is that this something

stimulated investment again, which in turn caused industry to need more

human labor, which in turn allowed private consumption to grow. The first

two long wave crashes were resolved by increased private investment

stimulated first by the building of the railroad grid starting in the

1840s, then later by the building of the highway and electrical grids

starting in the late 1890s. The crash of the third long wave did not have

an innovation, which encouraged direct private investment, and the only

stimulus was that provided by war later.

_________________________________________________________________________ Chart 4

10. Market Crash of 1987, the Internet and the Knowledge Wave Another potential depression-level crisis occurred in the fall of 1987, when the American stock market crashed deeply again. The then new chief of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, protected the financial system by providing large amounts of money for the banking system. This action was very necessary at the time, as the potential for a general depression was very great. Nobel economist Paul A. Samuelson believes that the crash could have led into another Great Depression: 'On

every proper Richter scale, the 1987 crash rivaled that of the 1929

crash. By contrast Samuelson seems to believe that the accelerated money supply in late 1987 probably was the difference, but that accelerated money supplies will not always work to resolve a crisis- as when a crash occurs against a backdrop of previously existing stagflation.[my emphasis] What Mr. Samuelson seemingly ignores in his criticism of the late 1987 projections by mainstream economists, is that they could not be sure that Mr. Greenspan would in fact dump enough dollars into the American banking system to keep the stock market crash from deteriorating out of control into a full-fledged depression. The previous chair of the Fed, Paul Volker, had engineered the economic collapse of the American economy in 1978 through high interest rates, wrecking whatever chances Jimmy Carter had had of retaining the presidency. Volker has maintained a deep suspicion of using government policy for dealing with economic crises and in fall 1987, no one could have been sure whether Greenspan would have had the ability to break with Volker and to use the monetary tools of the Fed: 'This

leaves me with the disturbing question of whether by using these tools [devices

for Moreover during November and December 1987, no one including Greenspan, could be sure that dumping large amounts of dollars into the American financial system would succeed in preventing a new depression. No more that we can be sure that a 1997 bailout of Korea similar to the earlier bailout of Mexico, will keep Korea from going further down and possibly dragging Japan down as well. Monetary policy is not always a guarantee in dealing with financial crises. Still, this single action did not restore private investment, although federal deficits continued at approximately the same level in 1988 and 1989 as in previous Reagan years. Greenspan kept the discount rate above ten percent for almost two years after the 1987 crash, waiting until mid-1989 to begin lowering it. However, private investment remained on hold for much of the next two years as the American economy basically sat dead in the water. Between 1989 and the end of 1992, Greenspan lowered the discount rate from about ten percent to about three percent and only in the last three months of 1992 did the economy start to register growth. Sadly for George Bush, the stirrings in the economy did not come soon enough to save his presidency. Then too, in 1987 there was no new innovation like point-of- production electrical motors on the assembly line in the 1920s, which could permit the capitalist system to begin dropping labor from production, even as production was held steady or increased. Thus Greenspan's 1987 loose money policy prevented the onset of a new Great Depression and his 1989 to 1992 loose interest policy helped guide the economy towards growth for the rest of the 1990s. It is a serious question as to whether either loose money or low interest rates would have salvaged the economy by 1994, had the Internet been as widely available as it later became after 1995. 11. Crisis in the Economy and Economic Theory However today a new crisis looms, in that the collective solutions to crashes three and four, have left modern economic policy in a severe bind. The collective federal debts from the 1940s until now have left the American economy water-logged and probably unable to run a third debt surge, comparable to the early 1940s or the early 1980s. Additional corporate and household debt from the 1980s and 1990s compound the problem. There is no new labor-intensive innovation on the horizon, capable of putting large numbers of unemployed back to work when the next crisis hits. Moreover, the Federal Reserve cannot again drop the interest rate by seven points, as it did between 1989 and 1992. Moreover this idea of the elimination of the business cycle seems baseless. Less than five years ago, a theory existed which claimed that the 'end of history' had occurred with the fall of communism. The 'end of the business cycle' theory will last until the next severe recession hits. Worse yet combination of the computer and the Internet, the only major technical innovations of the 1940s and the 1980s, actually threatens the currently existing labor-based job structure. And the currently evolving computer networks will shortly be interconnected in a way unimaginable even five years ago, rendering large numbers of current jobs redundant. 26 As the total wage structure begins to collapse with the interconnection of these corporate and government networks, the current labor-based monetary system will be unable to keep production and consumption in even approximate balance. At this point, a new form of demand will have to be created, or the entire modern economic apparatus may simply buckle and collapse. A synthetic wage structure will have to be created and funded, probably through the merging of fiscal and monetary policy. These synthetic wages will have to be issued to adult citizens, regardless of their participation in the labor market. And more crucially, the almost damning stigma associated with 'welfare' and welfare recipients must be eliminated, or the system will not work, regardless of the technical capacity of the new, evolving system. In a future society where no more than fifty percent of the adult citizens are required to produce the same or greater Gross Domestic Production as today, a whole new cultural outlook on wages will have to evolve and damned fast. 12. The Internet, Falling Rate of Profit and Knowledge-Based Accumulation Today, the crisis is unique to modern economics, in the sense that all previous interpretations of the business cycle and/or the long waves are probably out of date. 27 After five long waves, three labor-based and two debt-based, the first knowledge long wave looms. It has no readily apparent theory of value with which to replace the labor theory. And it may not act like any of the previous long waves, in terms of providing high profits for selected sectors and average profits for the other sectors of the economy. In many ways, the Internet may be seen as a vast 'falling rate of profit' mechanism, in that it seems to be almost congenitally hostile to profitability in the conventional sense of the word. The Internet is the perfect innovation for driving down overall profitability in the American economy. A recent article on Web bookseller Amazon.com illustrates this situation: The

Net, by its very nature is hostile to profit margins...Most

investors seem to And what is even worse, a knowledge-based economy may not even function as a long wave, the only type of capitalism, which has existed since the late 1700s. In many ways, a knowledge-based economy could be almost the death of capitalism as we know it, replacing large swaths of the professional classes, especially in the investment, media, entertainment and academic sectors. 29 This new type of economy has no historical precedent. It probably represents the accumulation of most societal information from myriad sources, into a comparative handful of very large aggregate databases. These very large databases are known as 'data warehouses' in the corporate world. Such databases would merge vast amounts of information onto large web-based systems. Sophisticated search engines and extensive indexing would allow access to needed information in much shorter times than previous. What is at issue is not another labor-based long wave cresting again, or even of a Great Depression-like problem, possibly resolvable by another 'debt-wave'. It is the rise of a non-labor-based economy, based increasingly upon the accumulation and distribution of goods and services through largely through the flow of knowledge over the Web. This type of accumulation is very different from the labor-based accumulation defined by Marx. It is also radically different from the debt-based accumulation model, which eventually developed out of John Keynes's theories. This knowledge-based accumulation may

require such drastic, sudden changes in the entire society, that simply

to broach them would make a writer comparable to an ancient biblical

prophet, discussing the fall of a society or laughably compared with

Chicken Little's astronomical views. Yet, as more and more of the

economy gets wired into the Internet-World Wide Web and as more and more

companies are created to support the shift to a knowledge-based system,

a serious question keeps arising. Where are the huge profits normally

associated with such changes in the capitalist system? In fact, where

are even average or minimal profits outside of a handful of companies

such as Microsoft? And even Microsoft's profits are largely a function

of its current monopoly control over the desktop. Such a transformation or transition to postcapitalism may seem difficult, but it must not be impossible, for such a failure may well send America and the globe back towards the 1800s, if not to the 1600s. _____________________________________________________________________________ Dates of Writing: Windsor Park, Valdosta, Ga. Ormond Beach, Fla. East 81st, NYC West 125th Street, NYC Broadway @ 50th Street, NYC ____________________________________________________________________________ 1 This process was

described as 'disaccumulation' by Martin J. Sklar in a 1968 paper in Radical

America. Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country:

Studies in U.S. History in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Cambridge,

Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 149-170. Back 4 James A. Caporaso and David P. Levine, Theories of Political Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 53. Back 5 Few original ideas exist in any field. And the development of any relatively original idea is seldom accomplished by any one writer. In the case of the long wave concept, other writers should be mentioned, especially Austrian Joseph A. Schumpeter. It was Schumpeter, far more than Kondratieff who saw innovation and the entrepreneur, as the source for new long waves. Kondratieff looked for a more internal explanation. I have conflated Kondratieff, Schumpeter and other writers under the rubric of the long wave, perhaps unfairly. For a longer more detailed discussion of the long wave model, see Ernest Mandel, The Long Waves of Capitalist Expansion and Late Capitalism. Mandel was a contemporary of Leon Trotsky and argued with him over the long wave concept. It was Mandel who first noticed the problems in capitalism which resumed during the mid 1960s and who interpreted those problems from a long wave approach. I should add that I believe his particular interpretation was inaccurate, but a version of the long wave hypothesis is in fact applicable to capitalism then and presently. Back 6 Irving

Fisher,"The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions", Econometrica

1, October, 1933, p. 337-357. [html to sections on Peter Temin and

Fisher] Back 11 The Economic Consequences of the Peace. Back 12 Joseph A.

Schumpeter,' Keynes, the Economist (2) in The New Economics: Keynes'

Influence on Theory and Public Policy, Seymour E. Harris (ed.), New

York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1949, p. 78, 79. This book was a collection of

essays by numerous members of the Keynesian establishment, shortly after

his death. Contributors included prominent economists of the era,

including Joseph A. Schumpeter, Paul Samuelson, Joan Robinson, Wassily

Leontief and Alvin H. Hansen, and a rising, future Nobel economist,

James Tobin. Back 16 Irving Fisher, The Stock Market Crash and After. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1930, page facing the title page. The Growth of Manufactures: 1919-1926 Compared With Preceding Two Decades. In a 1968 article, Martin J. Sklar would describe this situation as a 'disaccumulation' crisis, using similar data from the same Hoover Committee on Recent Economic Changes report used earlier by Fisher. Back Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 149-170. 17 See The New York

Times, February 21, 1998 article on Jean Baptist Say by Louis

Uchitelle. He noted that Say did not actually write the famous dictum 'Supply

creates its own demand'. Keynes used Say as an example of the

conventional economic thinking of the 1930s. Back 19 The collapse of the

Asian capitalist economies has led to a fresh use of terms popular

during the Great Depression, including the term 'liquidity squeeze' or 'liquidity

trap', even the term 'depression' itself. The Japanese economy has never

recovered from their stock market collapse near the end of the

Reagan-Bush years, when it fell from a level of about 36000 to less then

half, about 16,000. Today the Neisi Index is around 15,000. Back 22 See also Benjamin M. Friedman,'Views on the Likelihood of Financial Crisis', in Martin Feldstein, ed., The Risk of Economic Crisis, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991, p. 31. He has a chart of aggregate debt similar to RLNs, 1993. Friedman however takes a different view of aggregate debt. Back 23 Stockman was

Reagan's primary financial advisor during the early days of his

administration. Later Stockman became head of the Office of Budget and

Management. Back 24 Paul A.

Samuelson,'A Personal View on Crises and Economic Cycles', in Martin

Feldstein, ed., The Risk of Economic Crisis. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1991, p. 168-170. Back 26 [html connections

to sections on TCP/IP] Back "The U.S. economic experience in the early 1990s underscores Lamontagne's [Maurice, Canadian cabinet minister] point [Schumpeter's Three-Cycle model]: the "long cycle" is a paramount and very real concern for the United States. The long cycle of the 1990s is being driven not only by demographics but also by the federal government's deficit control". [my emphasis] Back Michael P. Niemira and Philip A. Klein,

Forecasting Financial and Economic Cycles. New York: John Wiley and

Sons, Inc, 1994, p. 303.

Your contact: peter.bretscher@bengin.com "A new Information Revolution

is under way. [...] |