|

A new economics and integrated business model is possible.

This is a non-authorized back-up-copy You may find the original at www.cfo.com

and more precise at http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/5491043?f=alerts

The New Human-Capital MetricsA sophisticated crop of

measurement tools could take the guesswork out of human-resources

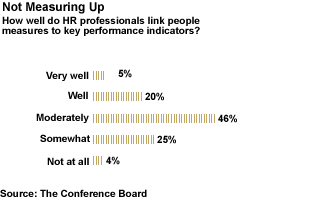

management. The human-resources department is in survival mode. As outsourcing the function becomes a more-prevalent option for companies, HR managers know that if they are going to endure, they have to deliver strategic value, and that value has to be measurable. With that in mind, many companies are forging ahead on efforts to create a new set of metrics that tie traditional HR functions like recruiting, training, and performance review to overall corporate goals — including fattening the bottom line. The old HR measures, such as head count, the cost of compensation and benefits, time to fill, and turnover, no longer cut it in this new world of accountability. They don't go far enough to create shareholder value and align people decisions with corporate objectives. The effort requires putting some hard science around issues that have traditionally been thought of as difficult to quantify, like why people leave the company or how engaged they are in their jobs. When realized, human-capital metrics can provide meaningful correlations that help predict behavior and human-capital investment demands well ahead of the annual budget. HR metrics might measure efficiency, or the time and cost of activities; human-capital metrics measure the effectiveness of such activities. Time to fill becomes time to productivity; turnover rate becomes turnover quality; training costs become training return on investment. "If your goal is to increase your company's people productivity through the effective use of human-resources tools and strategies, it's time to change the DNA of human resources," says John Sullivan, professor of management at San Francisco State University. "It's time to change human resources so that it focuses on top performers and ensures that it spends most of its time and budget on high-ROI activities." After all, he adds, "the only soft area left in a company is the largest expense item: people." While the mandate to measure has been around for some time, a Conference Board survey indicates that most companies aren't there yet. Of the 104 human-resources executives at medium- to large-size companies surveyed, only 12 percent make use of people measures to meet their strategic targets or key performance indicators (KPIs). But the message is loud and clear: over the next three years, 84 percent of that same group expect to increase the application of HC measures. It won't be easy. Mastering human-capital metrics is a complex undertaking. Linking people measures to KPIs in a reliable way can require massive amounts of data, and most efforts are technology-heavy. They require a good bit of trial and error, and a heavy dose of patience. And more often than not, a human-capital metrics initiative requires a good partnership between HR and finance. According to the Conference Board survey, collaborating with colleagues from finance was ranked the best way to build support for people measures, with 54 percent of respondents indicating that such a partnership is vital. The Labor Supply Chain Traditionally, managers at the 20,000-employee company would contact HR and request the number of people they needed, and the department would call recruiters and kick in the employee-referral program. And then "you prayed a lot," Hilbert says. By examining aggregate data on where people are hired from, how long they stay employed, how they fit in the corporate culture, and their level of individual productivity, "we've taken an art and we've made it a science," he says. Using that data, Hilbert is able to figure out where the company can recruit the best talent at the most affordable price. Valero can now determine for a specific project whether it's best — not just financially but also from a strategic perspective — to recruit full-time, part-time, or contract workers, or to outsource the work entirely. Valero also keeps scorecards of which labor sources provide it with its most productive employees and tracks it over the year. An upgrade to the company's HR Smart talent management software this year will also give the company a "global labor supply chain on demand," Hilbert says. The supply-chain approach to labor and detailed analysis of metrics also allow Valero to accurately forecast three years in advance its demand for talent by division and title. To accomplish this feat, the company dumped five years of historical people records into a huge database file, then consulted with Houston-based software vendor HLS Technologies to develop a series of mathematical algorithms for turnover trend analysis by location, position type, salary, tenure, and division. Those trends were projected forward through another series of algorithms, at which time Hilbert added numbers for the anticipated workforce for future capital projects, new systems, and services. "For the first time, talent pipelines can now be developed years in advance to meet specific future talent needs," he says. Training programs and succession plans can also be developed in advance. "It's pretty revolutionary stuff," Hilbert adds. Talent Scout Monteleone collected data on the productivity of each customer-facing employee and crossed it with the "pull-through rate," an industry KPI that measures how many customers who start the buying process actually complete it. He found that some workers were doing far better than others with their individual pull-through rates. Monteleone weighed several potential solutions, including changes to incentives, hiring, and training practices. He worked closely with CoreStar's vice president of retail sales, Kevin Ferguson, to gather data and simulate outcomes to determine which fixes would have the best business impact. "It's about capturing as much data as you can and organizing it so it makes sense," he says. "Something is going to stick, and you're going to understand a new metric." One option they considered, replacing the poor performers, was determined to be a dead end. Monteleone calculated that the company would lose about four weeks of productivity per person trying to replace a subpar performer and bring a new hire up to speed. In the end, CoreStar opted to invest in new IT infrastructure around call-flow management that not only monitors the pull-through rate better, but also better disperses the calls so that high performers field more promising calls and managers have more time to work with subpar employees to raise their performance level. As a result of the investment, Monteleone found that the sales team could take on more call volume at a lower cost to the company. "We were able to increase sales year over year by about 45 percent, but we only had to increase our sales force by 10 percent," he says. The shift from HR metrics to human-capital metrics owes much of its anticipated momentum to technology advances. Companies are increasingly relying on databases to gather and organize volumes of information about employees throughout their job life cycles. Online tools allow for prescreening and testing for competency and behavioral targets set by the company. Decision-makers use dashboards to select specific metrics from the database for analysis. Trial and Error Sysco Corp., a $32 billion wholesale food distributor based in Houston, found that its compensation system for drivers — paying them by hours worked — didn't provide as much value to the organization as it could. "The model didn't necessarily provide better customer satisfaction or profitability," says Ken Carrig, executive vice president of administration and head of HR. Instead, Sysco changed to a reward structure it calls activity-based compensation. Drivers earn a base pay that's supplemented with incentives for more deliveries, fewer mistakes, and good safety records. To be on the safe side, Sysco didn't roll out the program nationwide. It tested it in certain pilot markets first, and then tracked the results of the operating company. Four metrics were targeted: satisfaction level, retention, efficiency (delivering more cases in less time), and delivery expense. Under the new compensation structure, Sysco found that drivers were not only more efficient, they were also more satisfied. The company's retention rates for drivers improved by 8 percent, and expenses as a percent of sales went down. After quantifiable results showed the benefit of the change, Sysco rolled out the program nationwide. With 161 subsidiary companies, Sysco was also frustrated by the gap in HR performance at the operational entities. The executive team constructed a scorecard of a handful of metrics in customer, operational, financial, and human-capital areas, and then aggregated the data to show how subsidiaries were performing better in each measure. From there, Sysco developed a best-practices portal on the company intranet to share the results and build a healthy competitiveness. "If we had trouble with driver retention or shrink of inventory, managers would benchmark their results [internally]," says Carrig. As a result of implementing these practices, whether in human capital or elsewhere, a number of Sysco's companies moved from the lower 25 percentile to the upper 25 percentile. Carrig credits the support of the entire management team, especially finance, for making these changes possible. The controller team reassesses key metrics at least on a quarterly basis, narrowing a list of hundreds of different types of performance measures down to 25 or 30 and then to an executive dashboard of five to seven goals. At the meetings, senior management determines from the results whether the company is measuring the right ones and "what levers we need to pull," says Carrig. "Our CFO [John Stubblefield] values human capital and recognizes the need to quantify the work performed by our people. If I were the only one who thought it was important, it wouldn't get very far." Sysco is also piloting some new warehouse training techniques for new hires in 11 of its subsidiaries in the hope of accelerating their performance and tracking results over the next year. "If we don't see performance," Carrig says, "we'll call it a bad idea. Our metrics process is an ongoing evolution." Building up talent is also a priority for similarly named Cisco Systems Inc., the San Jose, California-based networking and communications giant. Karen Horn, Cisco's senior director of employee commitment, says the company recently added a metric that tracks why a person moved within the company to a dashboard of people measures that includes revenue per employee. Through that measurement, executives can spot which divisions in the company are creating new talent. It's the difference between just noting how many people moved and noting why. The why is where the value is, she says. Companies are increasingly measuring movement as a metric. High performers tend to want to take on new challenges, and businesses like to promote their best and brightest through the ranks. Tracking movement inside the company is also a way to make sure managers serve as talent "launching pads," rather than hoarders. Once identified, they can reward those managers accordingly. "The key is to find out which positions we need these superstars in," San Francisco State University's Sullivan says. The Human Factor Critics of human-capital metrics contend that people often defy metrics and that humans are too complex to analyze with reams of data and computer programs. Is it dehumanizing, for example, to apply a supply-chain model to recruiting? But not everyone agrees that human-capital metrics have a downside. Sullivan believes that anything can be quantified, but that fear motivates many to resist. "People in HR are resistant to measurement because they are afraid that they'll get an 'F', they'll get a zero," he adds. "If you're a top performer, you love measurement." Another drawback is that identifying which human-capital metrics are meaningful can be hit or miss. For this reason alone, it's not surprising that managers are hesitant to put too much time and energy into a program in which results may be few and far between. It's the "80/20 rule," Monteleone explains. "Twenty percent of the metrics will drive 80 percent of the business." Many companies struggle with just getting started, let alone keeping a program going for years on end. Jim Del Rosario, vice president of talent acquisition at Veritude, an HR services company in Boston, says it doesn't take a massive effort to get started on improving human-capital metrics. "You don't have to overanalyze or overengineer the metrics," he says. "Pick a few problem areas and figure out how to start measuring them." He says that when companies start planning a big-budget endeavor, managers tie one problem to another. "Measuring is more of an investment in time than dollars, and the return on that time can be immense," says Del Rosario. "Begin with one department or problem, then a bigger enterprisewide metrics program starts to evolve." Craig Schneider is a freelance writer in New York.  © CFO Publishing Corporation 2006. All rights reserved. Your contact: peter.bretscher@bengin.com "A new Information Revolution

is under way. [...] |